As Yemen enters its seventh year of war, humour in the form of self-mockery is emerging and thriving amidst the sustained state of horror. People grappling with the prolonged state of ruin and war are offering themselves as objects of mockery to connect and reconcile through shared lived experiences by laughing together at it. This is not only a modality designed for a fleeting catharsis but also a form of solidary mechanism in the face of everyday horrors inscribed in public memory. These attempts at self-mockery have the potential to become instruments to repatch a society together where war has torn apart most forms of sociality. In this research debrief, I examine a song that addresses the morbid daily horror posed by the paucity of cooking gas in the country through the device of sarcasm.

Peace beyond Liberal Peacebuilding

Dubbed a ‘political crisis’, the 2011 Yemen Revolution culminated in the adoption of a United Nations (UN) Security Council resolution that could not envision democratic peace in Yemen beyond the Gulf Cooperation Council Initiative. The 2013 National Dialogue Conference that followed was supposed to be an inclusive Yemeni-led process. Instead, it was dictated by Special Envoy Jamal bin Omar and ‘Friends of Yemen’ imposing prescriptions designed by international ‘experts’ that focused on the mechanisation of Yemen’s political elites, creating the world humanitarian crisis Yemen has become.1 Such approaches of peacebuilding should not be delinked from the United States’ (US) declaration of its Global War on Terror after 9/11 that relied on promoting an aggressive liberal agenda of economic and security reform, democratisation, human rights, combating insurgent groups, and state building, particularly in spaces interpreted as states on the verge of collapse.2 What the UN-led peacebuilding projects’ optimists (including President Abdu Rabu Mansour Hadi’s government and the international community) fail to see is how these schemes are a facade that nestles, secures, and sustains global, state, and elite powers.3 They are oblivious to these schemes’ counter-revolutionary character that ultimately seek to maintain the power of the powerful within a very limited, violent, and at times, sheer rhetorical frame of peace.4

What I explore here is a modality of peacemaking engaging with one’s brutal reality by laughing at it not only by way of seeking relief but also, ultimately, to signify a shared daily ordeal that can unite society. Peacemaking here does not refer to the refashioning of a subjectivity that conforms to the status quo. To make peace with daily war horror through laughter is rather a necessary move to be able to make sense of it, dwell and reflect on it, deconstruct it, and critique it; therefore, allowing the society to reconcile with itself. It connotes a form of peacemaking that does not conform to liberal peace; a form of peace that can only be initiated by Yemenis who have the capacity to deploy shared memory and cultural repertoire to regenerate sociality. It can be effective because it is staged at the margins, in hiding from authorities’ gaze, and therefore cannot be co-opted by institutionalised top–down liberal peacebuilding schemes. The laughter can escape appropriation because “laughter is an illusion since there are always only endlessly proliferating forms of laughter… that has a historically and culturally variable and instable significance”.5 What I am alluding to is the offering of self as an object of mockery and the collective laughter such an offering provokes. Laughter might sound alien when thinking about societies where wars have imposed economic, social, and political alienations, and social wreckage.

Many have attested to a darker side of laughter by looking into the ways comedy and tragedy, laughter and horror, mirth and violence are binary pairs that do not undermine one another but cohabit. In Freud’s pleasure principle, laughter has cathartic properties often geared towards dissolving anxiety and nervousness. Whilst a Freudian interpretation of laughter might seem to focus on its psychological cathartic effect, sociologists have examined the complex social, political, and cultural relations to which laughter insinuates. As Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin puts it, “Certain essential aspects of the world are accessible only to laughter”.6 Laughter does not only represent a society but also analyses it, critiques it, and reshapes the deviant. It unveils the tension and paradox that exist within a society. As Konrad Lorenz once stated, laughter is an instrument of inclusion, channelled to dissolve differences, yet it can be an instrument of exclusion that effectively erects boundaries around the aberrant, the immoral, and the corrupt.7 Through laughter, the taboo is confronted and the villain is exposed. And “for the joke to ‘work’ requires both shared knowledge and sentiment”.8 They draw attention to a shared identity and collective belonging to community.9 Importantly, it assures shared experience, allowing society to unite in laughter.

Privation of Cooking Gas

The US-backed coalition’s war against Houthis, and ultimately against Yemen, to restore the government of President Hadi has been, so far, successful in destroying Yemen’s economy and social fabric. The ongoing conflict between the warring parties has deteriorated the entire economy, imposed economic sanctions, increased the budget deficit, and devalued the Yemeni riyal (YR). Most civil servants have lost their income. Severe shortages of everyday life essentials have become the norm. The lack of cooking gas has become an aspect of daily aggravating encounters ordinary Yemenis experience because of war. Cooking gas cylinders have disappeared from their previous avenues of shops or hawkers, only to appear in abundance in the black market, where one cylinder can be purchased for 13,500 YR (US$12.00) against the actual value which is 500 YR (US$0.50). Many families have resorted to using firewood because they can neither find gas nor afford black market prices. While the war has played a significant role in this gas crisis, many also blame the rampant corruption of authorities and lack of regulations.10 Cooking gas is essential for small businesses (restaurants, food vendors operating from homes, minibuses, etc.) that emerged and operate at the margins of the collapsed economy.

The severe lack of gas has turned ordinary daily life into a nightmare, squeezing life and hope yet again out of these margins. In response to this daily ordeal brought about by war and political corruption, Anwar al-Sharafi and his band resorted to satirical songs as a way to make sense of, and speak back to, the daily horror the war brought about. The song “Ayn al-Ghaz?” (Where is the cooking gas?) questions authorities about the disappearance of gas from normal markets and its availability in black markets, while singing about the everyday horrors that culminate as a result.11 The clip’s music is borrowed from the children’s song ‘Baby Shark’ that went viral worldwide and became a rallying cray against government corruption in Lebanon.12

Laughing at the Horror of War

The song starts with the sound of a metal key pounding on a cylinder gas. This noisy gesture is meant to evoke a sound many Yemenis are familiar with. In the early morning, cooking gas hawkers often made this sound to announce their arrival with cylinders, while strolling down Yemeni alleyways and residential streets. Only those who either grew up in Yemen or lived there for long enough will appreciate this recognisable reverberation that disturbs the quiet mornings. The cylinder din can be cathartic yet petrifying. If a household has run out of gas, this noise simultaneously generates relief at the possibility of getting cooking gas and incites an unnerving sensation to jump out of bed and run to the street expeditiously in a race against time. To refill the gas cylinder, one must catch the hawker before either he or the neighbours who have taken possession of the few cylinders that he has carried in his wheelbarrow disappear.

As the pounding noise in the music video continues, a quad split screen with four clips emerges. One clip exhibits a distraught man in his backyard staring at an empty gas cylinder. The second displays a minibus driver and his gas-run bus pulling over as it is unable to drive his passengers to their destinations. The other two show anxious cooks in restaurants glaring at the cooking utensils on unlit stoves. Spooked by the lack of cooking gas, in a sense the suspension of life and livelihood, our four comic characters start screaming with horror invoking a San’ani vernacular expression “Ya’aw walfa’lah, ma besh ghaz!” (What a disaster, there is no gas!). This expression is commonly invoked when an unpleasant event strikes, but can also allude to a person witnessing their own entrapment in a dreadful or chaotic situation that can only be reflected as absurd. The best way to deal with this absurdity is to laugh at it, to laugh at one’s own entrapment in absurdity, to make peace with it, to make sense of it, and to seek catharsis. Nevertheless, this entrapment in war absurdity has become a collective and shared entrapment ordinary Yemenis animate.

As the pounding continues in the song, the music video shifts to a household where a father is fast asleep and his little boy is jumping on him to wake him up to catch the cooking gas hawker, but to no avail. The clip shifts to another house, where a husband, overwhelmed with panic, is pulled out of bed by his wife and pushed out onto the street with an empty gas cylinder as his wife waves her hands instructing him not to show his face without a refilled cylinder. He runs carrying the empty cylinder, hoping to catch the gas hawker. These scenes invite laughter simply because they are a shared nightmare almost every ordinary Yemeni husband, son, or father have come to experience; it is also the wrath of the matriarch in an otherwise patriarchal society that evokes amusement.

To the men’s tribulations, and as they run towards the rhythmic thumps, they are faced with the startling scene of almost everyone in the neighbourhood rolling empty gas cylinders before them, racing to get to the gas hawker first. As this banal everyday unfolds, shot in a comical style, they do not see a hawker when they arrive at the location of the pounding sound. Instead, they meet the neighbourhood official leader (‘aqil) standing with a pile of refilled gas cylinders behind him. The ‘aqil immediately utters the terrifying yet familiar “ma besh ghaz!” (There is no gas!).

What follows is a scathing critique directed at the ‘aqil, a symbol of existing political corruption that has contributed to ordinary Yemenis’ daily torment. The language invoked by the people is religious, demanding the authorities to bear the fear of God in mind and highlighting how the lack of cooking gas has brought their lives and livelihood to the abyss. The restaurant owner, minibus driver, an old housewife, and many others are also there. In bringing these people together in the mise en scene, the song seeks to represent the shared daily precariousness of as many segments of society as possible in the clip’s short timeframe. But the ‘aqil asserts “There is no gas!”, insisting in turn that the residents have driven him insane with their relentless complaints and that he cannot help despite the refilled cylinders piled behind him. The ‘aqil then claims that he himself could barely secure one gas bottle and accuses one of the residents of lying about not having cooking gas. Astonished by the blatant shamelessness the ‘aqil exhibits, the accused resident unveils the ‘aqil’s liesin a cynical manner that is meant to subject the ‘aqil to the horror of shame, inviting a collective laughter at him: a collective laughter that amounts to “spitting on the face of [corrupt] authority.”13

In the process, the accused resident divulges a rampant phenomenon of favouritism, where ‘aqils as figures of official authority – with many who are corrupt – hoard cooking gas and sell it only to their family members or friends. The music video ends when an old man walks to the arguing crowd, complains about their noise that has disturbed his peace, asks them to end the fighting, and disperses them with his stick. Then, the old woman who was complaining to the ‘aqil catches his attention and he flirts with her. Flattered by the attention, the old woman accepts the old man’s hand, ending the clip with the lightly humorous scene of the old couple united in a dance despite the horrors of war, lack of cooking gas, and ensuing social tension.

Making sense of shared war horror, generating reconciliation

The last scene of the music video extends an invitation to Yemenis to refuse social tension, resort to wisdom, and recognise the shared horror inflicted by war and corrupt politics. By marshalling shared memories and experiences, past and present, the video pleads to society to reconcile. The collective daily torment ordinary Yemenis live through, the music video pronounces, is not of their making. It is, rather, a collective entrapment in absurdity and the ugliness of war and political corruption that they can together make peace with, so as to collectively shame and laugh at it. These collective actions are meant to highlight the social bond that the shared daily turmoil establishes and sustains, urging a social reconciliation.

What this song and many other art works signify is that Yemen has traditional and cultural wealth, rich histories, and shared memories on which Yemenis draw to deploy reconciliation amidst Yemen’s fractured social realities. International and regional powers need to take their hands off of Yemen because most of the ingredients prescribed by them, to seemingly restore peace, have effectively led to conflict and strain rather than reconciliation. Until then, ordinary Yemenis will continue to birth and rebirth new avenues through which a reconciled Yemen may eventually emerge.

Kamilia Al-Eriani teaches at the School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Melbourne, Australia. Her research interests include state politics, modern violence, and alternative modes of ethical politics.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Yemen Policy Center or its donors.

German Federal Foreign Office

Copy editor: Jatinder Padda

Fatima Saleh (Arabic)

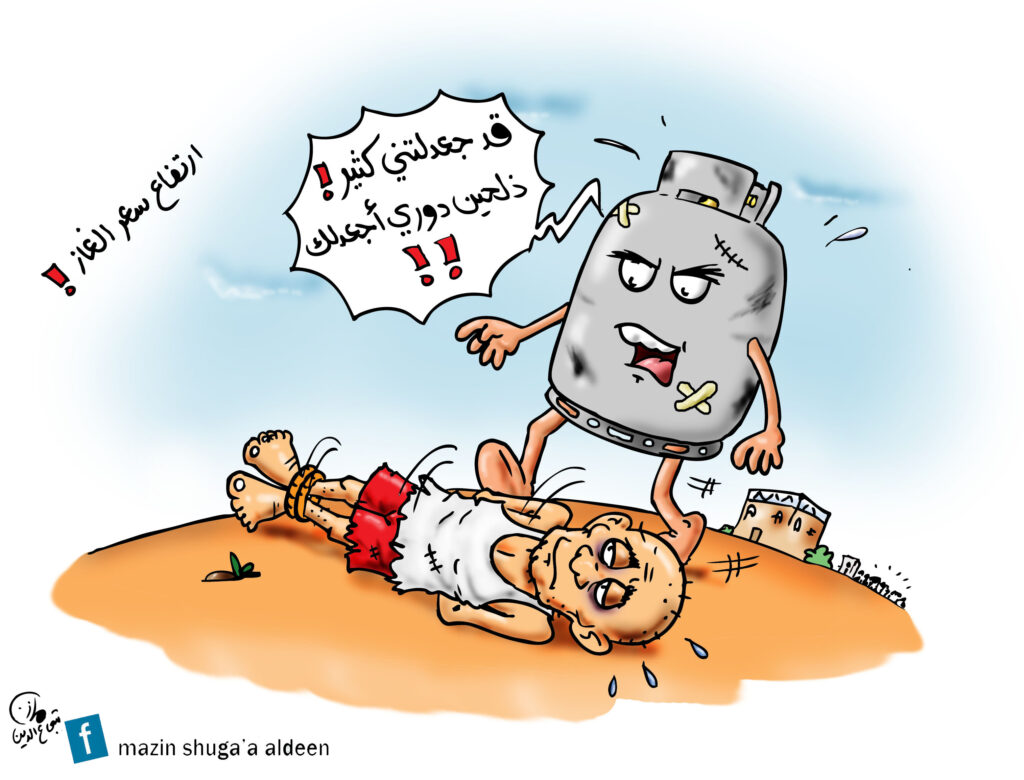

Caricature by Mazin Shuga’a Aldeen

- Kamilia Al-Eriani, ‘Mourning the death of a state to enliven it: Notes on the ‘weak’ Yemeni state,’ International Journal of Cultural Studies 23:2. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877918823774[↩]

- Thomas Maty-k, Jessica Senehi, Sean Byrne, Critical Issues in Peace and Conflict Studies: Theory, Practice, and Pedagogy. 2011. (Maryland, MD: Rowman & Littlefield)[↩]

- Moktary, Shoqi and Katie Smith, ‘Pathways for Peace and Stability in Yemen’, 1st ed. Washington DC: Search for Common Ground. 2017. https://www.sfcg.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Pathways-for-Peace-Stability-in-Yemen.pdf[↩]

- Oliver P. Richmond, Roger Mac Ginty, Sandra Pogodda & Gëzim Visoka, ‘Power or peace? Restoration or emancipation through peace processes’, Peacebuilding, 9:3, 243-257. 2021. DOI: 0.1080/21647259.2021.1911916[↩]

- S. Horlacher, ‘A short introduction to theories of humour, the comic, and laughter.’ In G. Pailer, A. Bohn, S. Horlacher, & U. Scheck (Eds.), Gender and Laughter: Comic Affirmation and Subversion in Traditional and Modern Media (pp. 17-48). 2009. Amsterdam: Rodopi.[↩]

- Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World Trans. Helene Iswolsky. 1968. (Cambridge MA: MIT Press), 66.[↩]

- Konrad Lorenz, On aggression. 2009. (London: Methuen).[↩]

- S. Swart, “The Terrible Laughter of the Afrikaner”—Towards a Social History of Humor. Journal of social history, 42(4), 889-917, 894. 2009.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- الحطب.. ملاذ اليمنيين في ظل ارتفاع سعر الغاز المنزلي الحطب.. ملاذ اليمنيين في ظل ارتفاع سعر الغاز المنزلي (aa.com.tr)[↩]

- Ayn al-Ghaz?” (Where is the cooking gas?): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tg4n34VFlxE[↩]

- Rabih Alameddine ‘Baby Shark’ and the Sounds of Protest in Lebanon The New York Times October 22, 2019.[↩]

- Moynihan, M. “The Laughter of Horror: Judgement of the Righteous or Tool of the Devil?” In Canini M (ed) Domination of Fear (New York: Brill), pp.173-190, 175. 2010.[↩]