Conflict has a devastating effect on education. It is a key factor in limiting access to quality education and has a negative impact on the mental health and productivity of children and youth.1 It also breaks down social cohesion and increases inequalities.2 However, one area of understanding conflict impacts has shifted from viewing conflict as an obstacle to providing education to more of an understanding of a subtle and profound “disturbing linkage”.3 Educational practices that promote cultural repression and manipulate culture and history to serve political goals can generate violence and reinforce inequality.4

Recently, the Houthis, ‘Partisans of God’, also known as Ansar Allah, introduced new changes to the school textbooks taught in primary education in areas under their control. The changes express their ideological, religious, and political views.5 During conflicts, education is forcefully politicized, and teachers, schools, and students become weapons and targets of war.6 The religio-political scene in Yemen was in a tumult during the last few decades.7 Before 1990, Yemen was two different states, south and north, the former led by communists and the latter in the liberal-capitalist camp. In the north and after the fall of the Zaydi8 Imamate, Sunni9 and Salafi10 Islam expanded even in areas dominated by Zaydi followers. Activities included establishing religious schools, which did not require any official approval. In 2000, Yemen had 1,200 theological institutes with 600,000 students.11 These institutes were supported by political parties and governments, for example Ma’ahid ‘Ilmiya (scientific institutes), which taught the Sunni doctrine, and were supported and dominated by the Islah12 Party, with the support of the central government and Saudi Arabia. Salafi schools also spread across Yemen, and their famous school, Dar Al-Hadith, was in Saada, the centre of Zaydi teaching. Zaydis in Sadaa saw such an expansion as a war on their Zaydi doctrine.

The establishment of Salafi schools in Zaydi areas posed a threat to the predominantly Zaydi population. This threat increased Zaydi followers’ interest in education as a defence mechanism to preserve their religious identity. In addition, after the revolution of 1962 in north Yemen against the Imamate, the ruling families who belonged to Al Al-Bait13 were excluded and stripped of power, which exacerbated their grief.14 1990 marked the establishment of two Zaydi Islamist parties, Al-Haq and the Union of Popular Forces, and educational institutes and camps15 which would have an active role in militarizing education. Religious infiltration, political-economic exclusion, and absence of government services in Sadaa became elements for Hussein al-Houthi, the leader of Ansar Allah, to catalyse a radical movement upon his return from his academic and religious education journeys in Iran and Sudan.16

It is, then, no surprise that Houthis have deployed education to reinforce both their identity and legitimacy since the outbreak of the 2015 conflict, when the Saudi-led coalition announced its war against the group, as the conflict has mobilised doctrinal differences (Zayidi-Shiite vs Salafi and Sunni Islam) as another milieu of war.17 The changes introduced to school textbooks in areas under Houthi control serve to ‘deepen faith identity’18 and reinforce claims of fighting Western imperialism, and its regional and local puppets. Additionally, the Houthis are forcing certain practices in schools such as prohibiting gender mixing and the replacement of entertainment songs with Houthi slogans and religious anthems and hymns.19 The new changes reflect political and ideological ambitions and seek to establish a hegemonic discursive knowledge to shape a public and political order that normalizes violence and conflict and to legitimize the ideological and political vision of the Houthis.

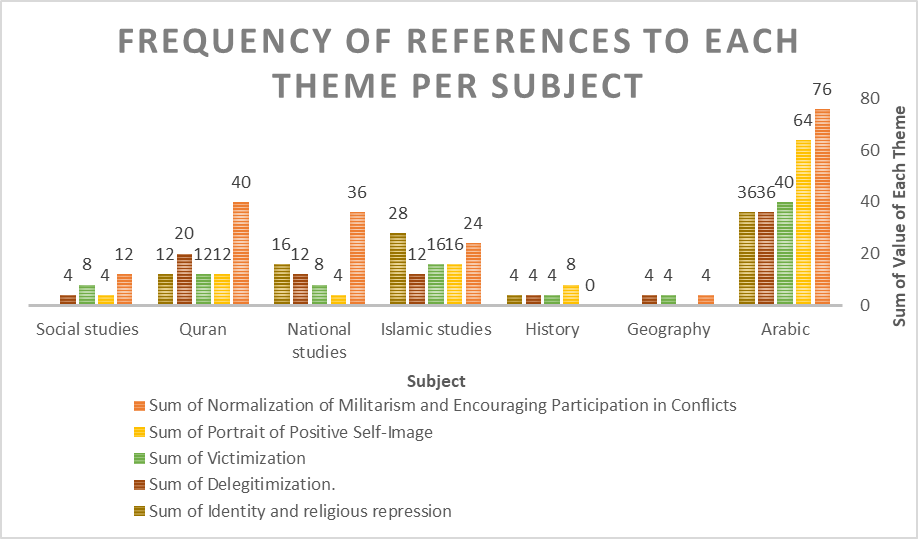

This debrief utilizes thematic analysis using a qualitative approach. This approach allows for a proper elaboration on the themes emerging from the data.20 The research explores how textbook changes have the potential to escalate conflict and devalue efforts towards peace. It analysed 57 textbooks from grade 1-9 (age group 7-16) on the following subjects: Quranic studies, Islamic studies, Arabic, and social studies (which includes geography and history).

The Negative Face of Education

School textbooks represent the foremost form of societal ethos transmitters. They are used as mass ‘interference’ between an authority’s ‘acceptable culture’ and students.21 Textbooks are considered authoritative and factual.22 Politically influenced education is often exclusionary as it fails to represent different collective national identities. Political mobilization through education can promote social division, and eventually violence against certain groups and increase structural violence.23 Structural violence is a “situation in which unequal, repressive, and racist forces are in the structures of society”.24 Violence is not a normal response to disagreement, but it is generated by widespread anomie and manipulation by elites who have the power to reform educational systems. For instance, and as observed elsewhere, history education has the power to construct identity and the ability to create imaginary communities based on the narrative provided about the ‘other’.25 This can be reinforced through emphasizing the “sectarian identities offering negative and stereotypical images of the other, and naturalizing the victimhood or superiority of particular groups”.26

Such power can be observed in Yemen. In the last four years, school textbooks used in areas under Houthi control have undergone ideological and political changes. Textbooks are loaded with materials that promote zero sum conflicts, where there is always a losing side that should be eliminated. They seem to function as a tool for values inculcation, political socialisation, and obedience cultivation. More recently, as Yemen has moved towards dialogue and negotiations, many political dynamics hint at the coalition’s desire to move towards relinquishing conflict. Yet changes, including in education, by the Houthis allude to a long-term vision where prospects for peace are absent, perhaps prompted by a desire to continue to be the primary authority in the north. These changes might have far-reaching effects on children, who are the seeds for any prospects of peace; particularly when conflicting parties have no hesitation in recruiting child soldiers.27 The following four sections look at some of the ways in which school textbooks are altered to inculcate the chosen ideology.

Constructing a Positive Self-Image

Houthis claim that they have a divine right to rule the ‘Umma’, referring to the Islamic nation, and lead in all areas of life. This was part of the 2012 document issued by their leader, Abdul-Malek al-Houthi, which highlights:

“We believe that God Almighty elected the house of the Prophet and made them guides to the Umma and inheritors of the holy book after the Messenger of God until the day of judgment, and that in every age, He prepares one to be a guiding light for His worshippers, one able to lead and champion the Umma in all its needs.”28

The new changes in the textbooks stress such beliefs through exulting the Houthis’ religious and political leaders as the descendants of Prophet Mohamed (Al Al-Bait) to construct a legitimate and positive self-image. The changes hail the efforts of their own leadership and fighters, glorifying them as creators of Yemen’s history. Across all the analyzed textbooks, the books portray a positive and heroic image of the fighters. Simultaneously, they give a negative image of the ‘other’, the ‘traitors’, referring to the Internationally Recognized Government (IRG) who sold their souls for money to the Americans, Saudis, Emiratis, and Israelis. They also use demeaning vocabularies, claiming that their opponents have no moral worth, and that they are trying to destroy Yemeni culture and its Islamic principles. A grade-6 Arabic textbook mentions two poems that extol ‘Mujahideen’ heroism in fighting the remnants, the ‘tails’ (a derogatory term referring to other Yemeni warring parties supported by Saudis and Emiratis, to invoke the notion that they are an extension of the Americans, Saudis, and Israelis powers). In grade-7, an Islamic studies textbook poem on Al Al-Bait is inserted, urging people to follow them, “for those who follow them will never lose”.

These changes romanticize militant rhetoric, masked in an Islamic garb. For example, ‘Mujahed’29 is linked to a positive heroism and chivalry to signify those who fight for a just Islamic cause. ‘Shahid’30 is linked to sacrifice and selflessness in serving Islam and protecting people. It also utilizes social and family relations. Jihad is portrayed as an obligation handed down from fathers to sons, and Shahadah presented as hereditary. For example, in a grade-5 Arabic textbook, there is an image of a father with his two sons shooting using rifles, normalizing the idea that children should follow their father’s steps. In a grade-7 Quran textbook, an entire ‘Surah’31 is employed to explain the heroism of participation in Jihad to defend the country and the weak from invaders and traitors (who are considered in this narrative as the Muslims traitors who follow the Americans and Israelis).

The way these new changes stress glorifying ‘child soldiers’ is worrying. On many occasions, they explicitly describe how children manage to destroy strategic targets, shifting the balance of power in the battle to the Houthis’ side. For example, in a grade-6 Arabic textbook, a unit which consists of five lessons discusses ‘The Greatest Martyr’, which is a narrative about a child soldier, born in Sadaa, who managed to destroy a target by suicide bomb, eventually changing the trajectory of the battle.

Identity and Religious Repression

Education in general has always been contrived to benefit political powers as it is considered an ideological tool for indoctrination and a means that can be manipulated to embed values and encourage certain attitudes to either condone or exacerbate violence.32 This can manifest in identity construction and destruction. New changes in the inspected texts have a tendency for religious repression and identity homogenization. Some events, places, and figures have been removed and replaced by others that fit the Houthi narrative. For example, Ali Ibn Abi Talib and Fatima33 are repeatedly mentioned, while other Islamic figures are omitted or their role in Islamic history is presented as less important, such as Aisha, the Prophet’s wife, Abo-Bakr, and Omar Ibn Al-Khatab, who are followed and respected by Sunnis. In addition, there is a focus on respecting and idealizing Al Al-Bait in all the primary classes textbooks. For example, a grade-9 Islamic text states that the first question Allah asks on resurrection day is “Do you love Al Al-Bait?”. Another text emphasises that following Al Al-Bait is a religious obligation.

The Houthis’ claim to represent Al Al-Bait aims to construct their identity as superior, giving them a holy right to be followed and to sanctify their acts. The texts mention some of the Houthis’ deceased leaders as ‘martyrs’. Other figures who do not affiliate with their political views are erased. Further, the Houthis seek to establish uncontested religious rights to justify the excessive extraction of money from Yemenis. In a grade-8 Quran textbook, they employ a Qur’anic verse to insinuate that what was taken in wars ‘as booty’ without fights belongs to Al Al-Bait. These changes establish their political legitimacy as a divine right that neither should be rejected nor negotiated.

Recent changes in textbooks deploy the recent past and transform it into an ‘active past’, which can serve as a starting point for political legitimacy. The textbooks discuss the contemporary conflict and the Houthi takeover of Sanaa in 2014 as a second revolution, to articulate a ‘starting point’ of history written anew and to shape students’ political views. For example, they labelled the 11 February 2011 Arab Spring as a failure and presented 21 September 2014 as a correction revolution, cancelling others. Furthermore, the textbooks mentioned Sadaa, the ideological capital of the Houthis, more than Aden and Sanaa, the economic and political capitals of pre-2015 Yemen.

Some scholars suggest the use of “history, myths, memories, and religious narratives” provide the ground of diabolizing the ‘other’ as a threat to existence,34 reshaping shared social affinities and cognition. This social cognition can eventually lead to acts of violence. In the analysis we will see that history, particularly Islamic history, has occupied a huge part of the curriculum, as these themes are taught in the Quran, Islamic studies, Arabic language, and social studies textbooks. Unlike biology or science, these textbooks offer a space for retelling historical events, omitting certain events and characters, and manipulating shared knowledge. It provides a valuable opportunity for the dominating power to manipulate shared knowledge and employ social cognition for political gain.

Normalizing Militarism and Encouraging Participation in Conflicts

In a war zone like Yemen, militarism and violence have been normalized through school education. Such normalization draws from military doctrine whereby every child is considered a probable future soldier. The texts explicitly discuss violence but, interestingly, neither the causes nor consequences of violence are explained. Violence is frequently presented positively, either as a normal social and familial response to conflicts or as part of daily practices. For example, in the Arabic grade-5 textbook, two lessons talk about wounded combatants and what is expected from children toward them, as if it is everyday customary practice. Furthermore, the texts utilize poems to normalize the conflicts. Poems are easy to memorize and reiterate even outside schools. For example, in a grade-2 Arabic text, a short poem is printed on the cover that encourages participation in conflicts as an obligation to defend the country. In a grade-3 Arabic textbook, a poem appears with a picture of a soldier holding a portable rocket launcher, praising participation in conflicts and defending the country.

To normalize weapons and violence, textbooks used pictures of weapons, deceased children, bloodshed, and militarizing narratives in a repetitive manner across all 1-9 grades. The use of these pictures potentially perpetuates violence as a natural response to conflicts and as an unfortunate process that Yemenis must endure to protect their religion, culture, and land. In a grade-1 Quran textbook, there are pictures of the ‘Mujahedeen’ army with heavy artillery with a caption of ‘Al-Mujahedeen defend their country’. The fact this was discussed within a religious frame gives extra righteousness and virtue to the conflict, making violence inevitable to achieve a ‘holy cause’.

The textbooks are designed in a very selective manner, yet with a lack of coordination between narratives. The aim is to design religio-political narratives that align with their agenda. The grade-6 Arabic textbook has eight lessons which discuss the ‘martyr leader’ Hussien Badr Al-Deen Al Houthi: his life, death, and fight against the ‘Americans and their allies’. Following these, eight lessons on the Palestinian-Israel conflict are introduced. The textbook attempts to establish a relationship between the Palestinian struggle and the Houthi struggle in Yemen. Establishing this connection to fit a certain theme is repetitively used in the Arabic textbooks. While the textbooks are stoking pro-militarising messages, there is a stark absence of messages that promote peace. On the contrary, grade-8 Islamic studies textbooks urge learners to refuse negotiations and ‘half solutions’.

Textbooks depict supporting the current conflicts, financially and/or physically, as a religious and sacred practice. In the grade-3 Arabic textbook, a lesson explains the virtue of financially supporting the ‘Mujahedeen’ through a story of a father praising his son for doing this generous and thoughtful act. The grade-7 Arabic textbook includes a lesson on the heavenly rewards of the warriors in the war fronts that is packed with Quranic verses that have been taken out of their historical context. Furthermore, in part 2 of the grade-6 Arabic textbook, the cover of the book and an entire unit consist of more than one lesson about a child solider who was killed during the ongoing conflicts. The textbook tries to venerate his ‘sacrifice’, and it also encourages children to do the same. Occasionally, the textbooks encourage students to go to summer camps and Friday prayers, which are currently used for military recruitment and anti-coalition rhetoric.35

Victimization, and the Delegitimization of Others

Reading across the textbooks, one can trace a systemic approach that creates a societal memory of what religion, history, and culture consider as ‘common sense’. The textbooks place Yemenis as victims, portraying the world outside Yemen as a force that seeks to exploit Yemeni resources and destroy its religion and culture. They are also using the Palestinian struggle as a model of victimization in a notion that their conflicts are an extension of the Palestinians’. After establishing this societal image, the textbooks go further, to give legitimacy for their violence, denoting how despite being victims they heroically defend Islam and the weak in Yemen and beyond.

Lessons of victimhood predominately appear across all nine grades. A grade-9 geography textbook mentions the Emiratis’ takeover of Socotra Island, and the coalition ‘Al-Eduan’ stealing oil. In the same grade, a Quran textbook includes an exercise that asks students to talk about ‘Shahid’ or a martyr that they know. Relatedly, in a grade-7 national studies textbook there is an exercise that asks students to discuss and watch children who died because of air strikes led by ‘Aladwan’. Such examples promote a victimhood narrative.

Simultaneously, demonizing the international community, Western countries, and the coalition is at its highest. Across all the grades there are 21 textbooks that significantly delegitimize other military camps and international actors, only to reconstruct their legitimacy. For example, in a grade-8 Quran textbook, an exercise revolves around video clips of al-Eduan troops fleeing, insinuating that they are cowards, deserters, and hypocrites (referring to the government supported by Saudis). Similarly, in a grade-6 Arabic textbook, a poem titled ‘My country and the neighbors’ condemns Muslims who follow the Americans, Israelis, and Saudis and promises them enormous losses.

Opportunities in Education Investment

Schools are not a static entity, they are the real manifestation of the communal dynamics, and they are one of the places, along with mosques and universities, where people from different neighborhoods congregate and where ideas, behaviors, and personalities are made. Education provides an opportunity to mobilize people which awaits investment, or at least that is what the Houthis did. If that opportunity is not properly utilized, for example to promote peace, it will always be part of instigating the conflicts.

Today’s violations could be tomorrow’s conflicts, so instead the past, present, and future must be reconciled. To convince political parties to spare education from being politically and ideologically manipulated, there should be work towards preserving the history, culture, identity, and dignity of all the different sectarian and political parties. In addition, human rights violations should be documented without manipulation to enable a transitional justice that can restore a cohesive societal memory.

Education cannot wait. Providing equitable quality education starts with ensuring that education improves children’s skills and well-being equally and does not contribute to conflicts. Donors and nongovernmental national and international organizations need to work ‘in conflict’ not ‘around conflict’. This requires their attention to support educational reform now rather than waiting until war is over. This can happen by conducting an evaluation of the current textbooks across Yemen and their contribution to instigating/ mitigating conflicts. A joint Task Team that represents all Yemeni communities led by neutral parties should be assigned to examine and rewrite textbooks as necessary. The evaluation should point out what should be changed to improve the quality of education. Accordingly, based on the findings, textbooks should be changed in the country.

Peace education classes and textbooks should be part of Yemeni education, disseminating reconciliatory messages and Islamic and tribal traditions. Introducing and promoting peace in schools will diminish the impact of the politically ideologized textbooks. Using alternative educational sources and establishing nontraditional learning methodologies in Yemen would reduce the authoritarian impact of textbooks, allowing for opportunities to increase the quality of skills and knowledge children receive.

We must include education in the peace talks. Peace initiatives should not underestimate the power of education in steering peace. Including education in peace talks will put pressure on all war agents to neutralize education, which can create mutual ground for peace across the country.

Unless challenged, other conflict actors will use education in the same way. Due to the contested nature of education and the current changes in school textbooks in areas under the control of the Houthis, it is foreseeable that other political parties will do the same. Especially in the south of Yemen, where the Southern Transitional Council (STC) is making claims for power. Going forward, there should be separate talks with the IRG and the STC and other political actors to spare education from political influence.

Malek Saeed joined the Yemen Policy Center as an Associate Fellow in 2022. His research focuses on political contestation in education and its impact on the course of conflicts. Malek has built his career working with international NGOs in education and with ministries, educational offices, schools, and Yemeni communities in different governorates.

German Federal Foreign Office

Kamilia El-Iriani

Mareike Transfeld

Jatinder Padda

Enas El-Torky

Ahmed al-Hagri

- Mieke Lopes Cardozo and Mario Novelli, “Education in Emergencies: Tracing the Emergence of a Field,” in Global Education Policy and International Development: New Agendas, Issues and Policies, (2018), p. 233.[↩]

- Patricia Justino, “Barriers to Education in Conflict-affected Countries and Policy Opportunities,” (UNESCO, Institute for Statistics, 2014).[↩]

- Sobhi Tawil and Alexandra Harley, “Education and Identity-based Conflict: Assessing Curriculum Policy for Social and Civic Reconstruction,” (Education, conflict and social cohesion, 2004).[↩]

- Kenneth D. Bush and Diana Saltarelli, “The Two Faces Of Education in Ethnic Conflict: Towards a Peacebuilding Education for Children,” (University of York, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, 2000).[↩]

- Anef Taher, Zafar Khan, Ahmed Alduais, and Abdulghani Muthanna, “Intertribal Conflict, Educational Development and Education Crisis in Yemen: A Call for Saving Education,” (Review of Education, 2022), p. 13.[↩]

- Bilal Barakat, Zuki Karpinska and Julia Paulson, “Desk Study: Education and Fragility,” (Oxford, UK; interim submission presented by Conflict and Education Research Group and Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies Working Group on Education and Fragility, 2008).[↩]

- Mark Corcoran, “Timeline: A Century of Conflict in Yemen,” ABC, 2015, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-04-15/yemen-a-century-of-conflict/6381720.[↩]

- Zaydism is a sub-sect of Shiite Islamic doctrine, which is distinctly different from the sect that is practiced in Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon.[↩]

- Sunnism is one of the largest sects of Islam, and it is different from the Shiite sect.[↩]

- Salafism is a reformed sub-sect of Sunnism that advocates for the return to the traditions of the first Islamic generations.[↩]

- Fawzi Al-Ureyqi, “The June 13 Movement and the Theological Institutes,” Khuyut, June 15, 2020, https://www.khuyut.com/blog/06-14-2020-09-43-pm[↩]

- Islah is a Yemeni Islamist Party that was formed in 1990 and affiliated with the Muslim brotherhood.[↩]

- In this debrief, Al Al-Bait refers to the families who believe that they are the descendents of the Prophet Mohammed.[↩]

- Adel Mujahed, “The war of Sayd and Shiekh in Yemen,” Assafiralarabi, 2014, https://assafirarabi.com[↩]

- Maysaa Shuja Al-Deen, “Yemen’s War-torn Rivalries for Religious Education,” (The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2021).[↩]

- Peter Salisbury, “Yemen and the Saudi-Iranian Cold War,” (London: Chatham House, Royal Institute of International Affairs, February 2015), p. 5.[↩]

- Kamilia Al-Eriani, “The Houthis and the (In)Visiblity of Piety: Reorienting Piety in North Yemen,” Jadaliyya, May 11, 2021, https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/42714[↩]

- “Discussing the Requirements for Consolidating the Faith Identity in Technical Education Institutions,” https://althawrah.ye/archives/659279[↩]

- Ahmed Nagi, “Education in Yemen: Turning Pens into Bullets,” (The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2021), p. 4.[↩]

- Klaus Krippendorff, “Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology,” (Sage, 2018).[↩]

- Allan Luke, Literacy, Textbooks and Ideology: Postwar Literacy Instruction and the Mythology of Dick and Jane (Bristol, Taylor and Francis, Inc, 1988).[↩]

- Jean Anyon, “Ideology and United States History Textbooks,” (Harvard Educational Review, August 1979), pp. 361-386.[↩]

- If we look at the current conflicts through structural violence, we can extrapolate to some extent that Ansar Allah and other current active military powers emerged due to the structural violence practiced by the previous regime.[↩]

- Peter Uvin, Aiding Violence: The Development Enterprise in Rwanda (Kumarian Press, 1998).[↩]

- Benedict Anderson, “Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism,” in The New Social Theory Reader (Routledge, 2020), pp. 282-288.[↩]

- Davies Lynn, Education and Conflict: Complexity and Chaos (London: Routledge and Falmer, 2004).[↩]

- Edith M. Lederer, “UN: 2000 Children Recruited by Yemen’s Rebels Died Fighting,” APNews, January 2022, https://apnews.com/article/middle-east-united-nations-yemen-houthis-17c3e19c239be8a2f41ee3e27469fc6e[↩]

- ACRPS, “After Capturing Amran, Will the Houthis Aim for Sanaa?”, Doha Institute, 2014, https://www.dohainstitute.org/en/lists/ACRPS-PDFDocumentLibrary/Yemen_Houthis_Amran_July_August_2014_Assessment_Report.pdf[↩]

- Mujahed and Jihad are Arabic words that is used to denote the fighter who fight for faith or Islam good cause[↩]

- Shahid and Shahadah are Arabic words that mean martyr in Islam.[↩]

- Surah is an Arabic word which comes from the Quran and it is the name of a group of verses; there are 114 Surah in Quran.[↩]

- Alan Smith, Education in the Twenty‐First Century: Conflict, Reconstruction and Reconciliation (Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 2005), pp. 373-391.[↩]

- Ali Ibn Abi Talib is a cousin of the Prophet Mohammed; Fatima is the Prophet’s daughter and was married to Ali who the Shia follow. In Arabic, Shia Ali means the followers of Ali. For more details, see A Primer to the Sunni-Shia Conflict.[↩]

- Susanne Buckley-Zistel, “In-between War and Peace: Identities, Boundaries and Change after Violent Conflict,” (Millennium, 2006), pp. 3-21.[↩]

- Ahmed Nagi, “Education in Yemen: Turning Pens into Bullets,” (The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2021), p. 5.[↩]