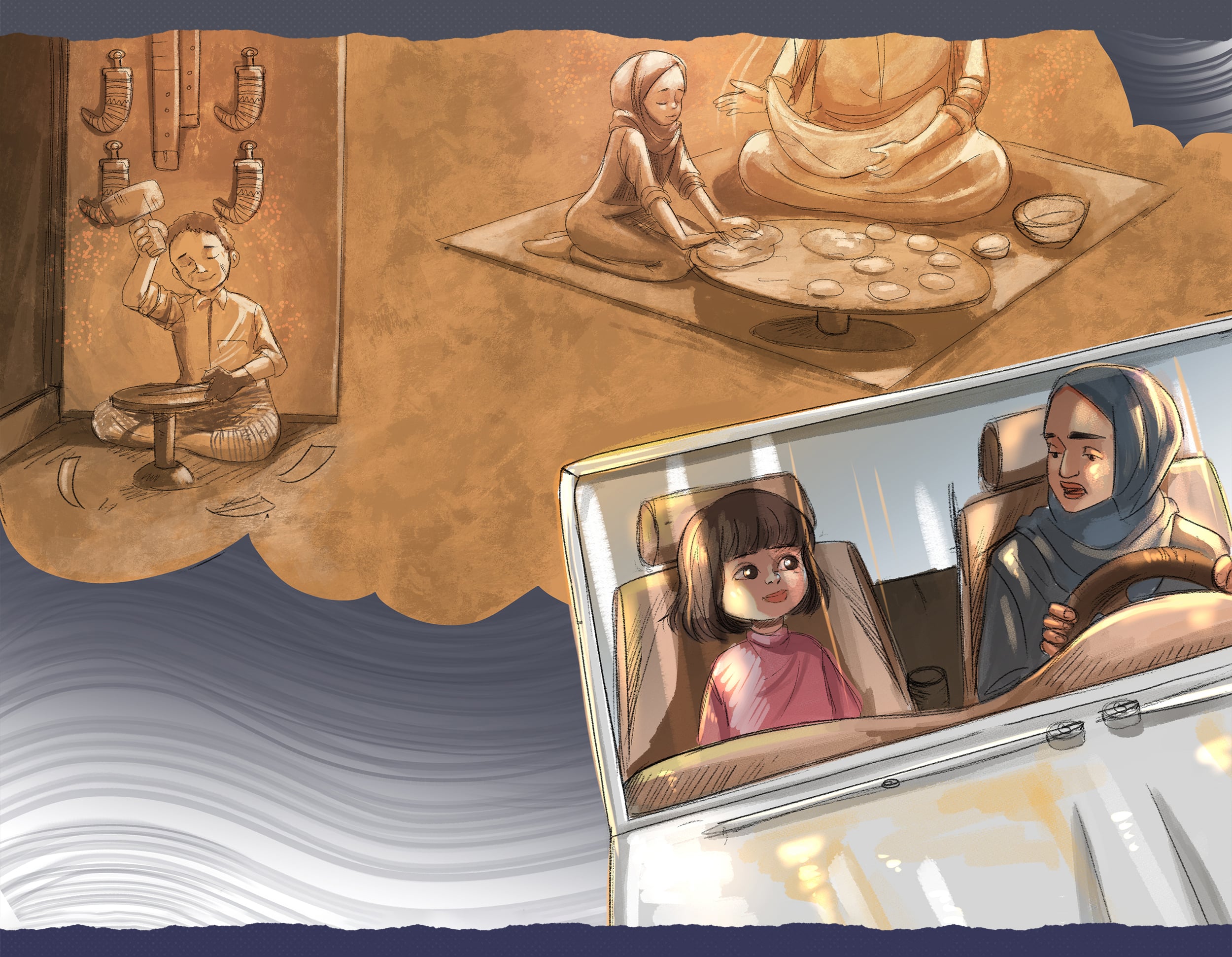

“I don’t want to go to school tomorrow!” The sentence every mother dreads. Its Saturday, the last day of the weekend before my nine-year old daughter Lamma returns to school and I to work. I call Sunday the “hard day”—getting back to business after the weekend is never easy, and today has been equal parts exhausting and exciting. But this time, it’s something else. Lamma’s voice—normally so assured— is hesitant, faltering even. I wonder what’s going on with her.

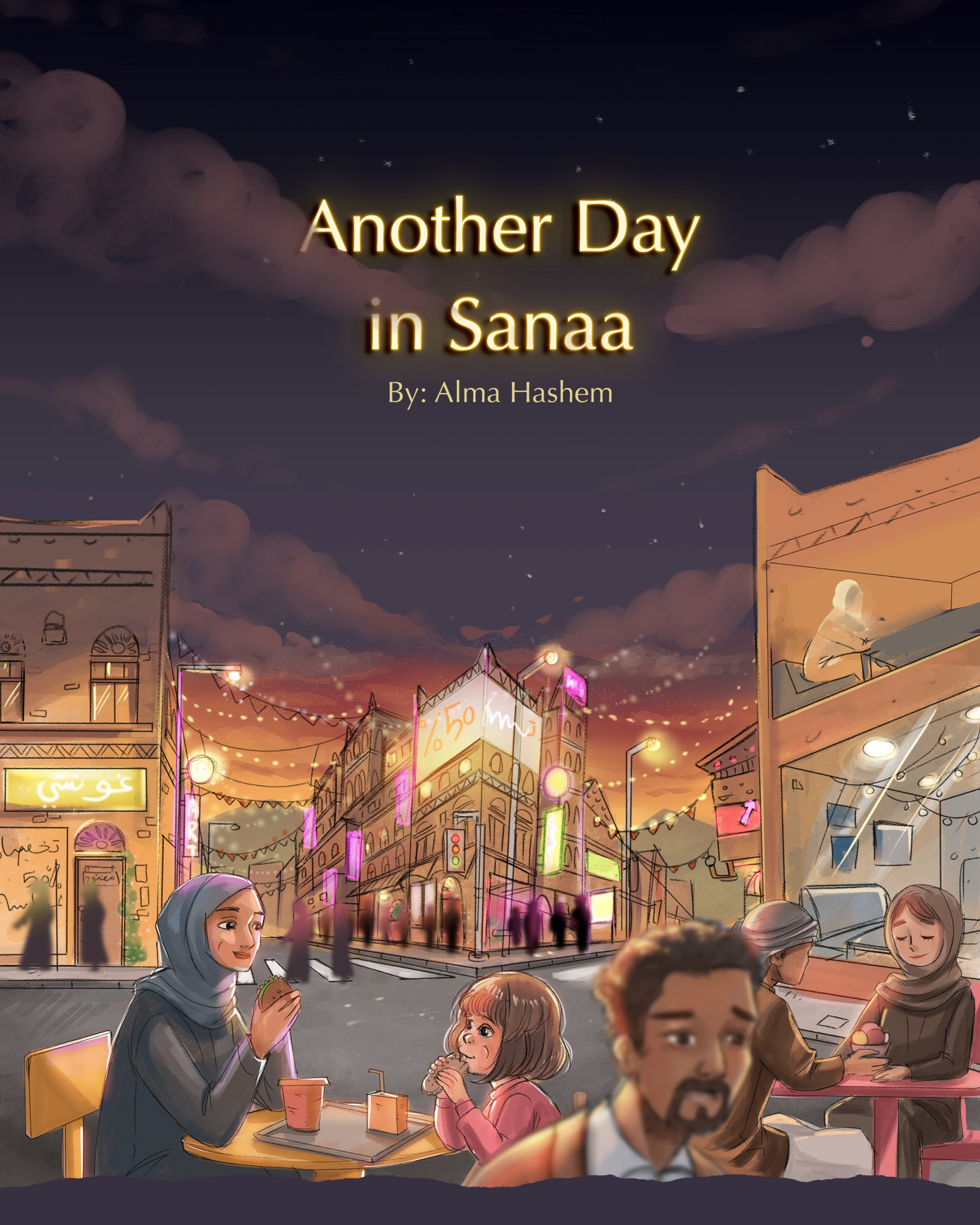

We decided to attend a ballet recital at the Rainbow Theater. My daughter dances ballet on the children‘s national team, so we always get invited to the performances. I love these perks. After the show we are starving, so we have dinner at a restaurant that opened last week. It’s a new international franchise conveniently located in Zone 2, an area previously called Bait Baws Square.

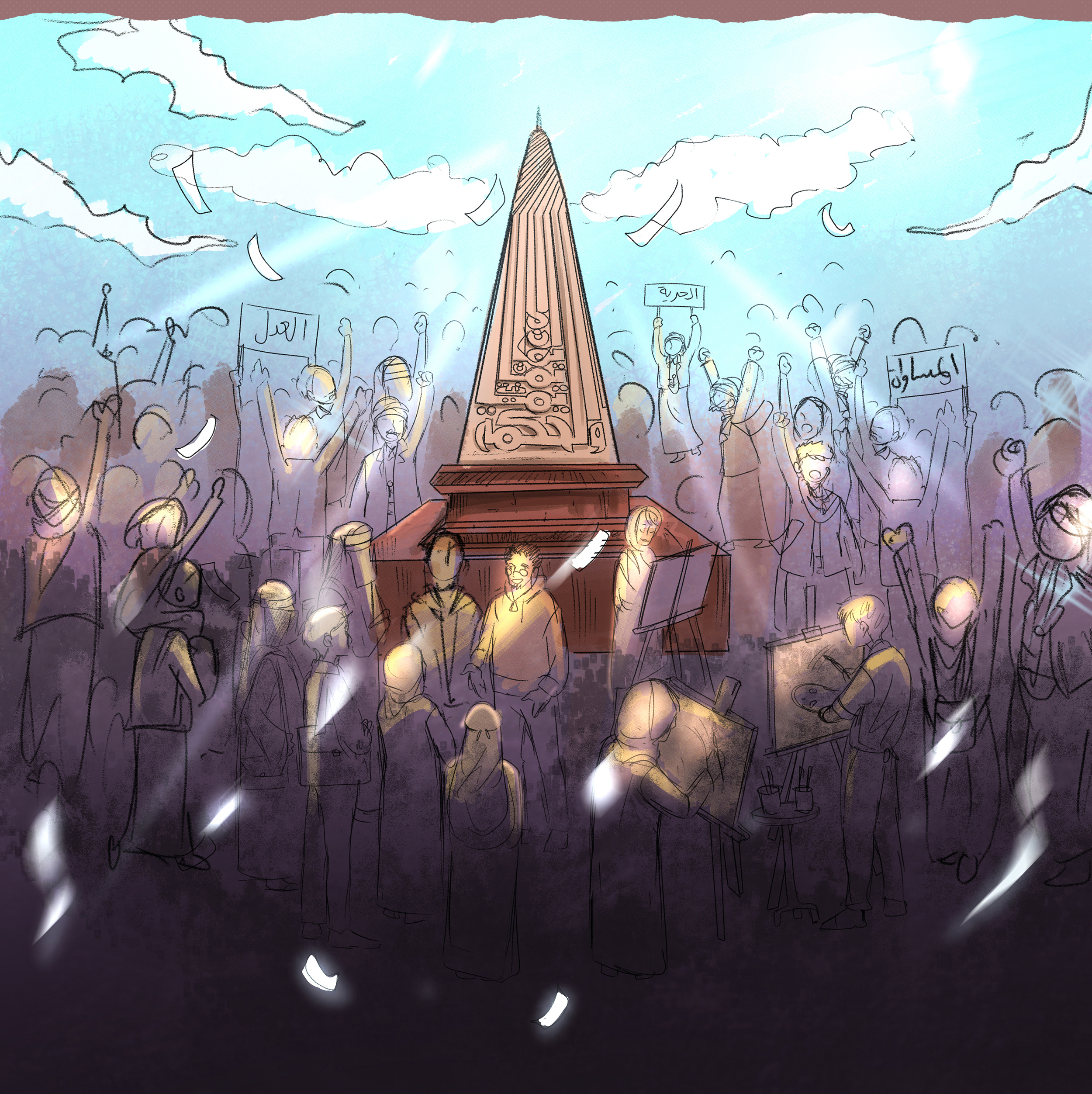

The entire area was revamped and it’s now a real entertainment destination, with everything you could possibly wish for door to door: restaurants, parks, a big cinema, a theater. Major brands stand alongside the creative artisanal shops that I love. Sipping on my Nana lemon as I waited for my sandwich, my glance falls on a large digital billboard across the square. From the porch where we are sitting, I can only make out a part of the screen (the rest is blocked by the large fountain). But I don’t need to see the entire screen to know what’s playing: videos of the Revolution of 2011. It’s the 10th anniversary.

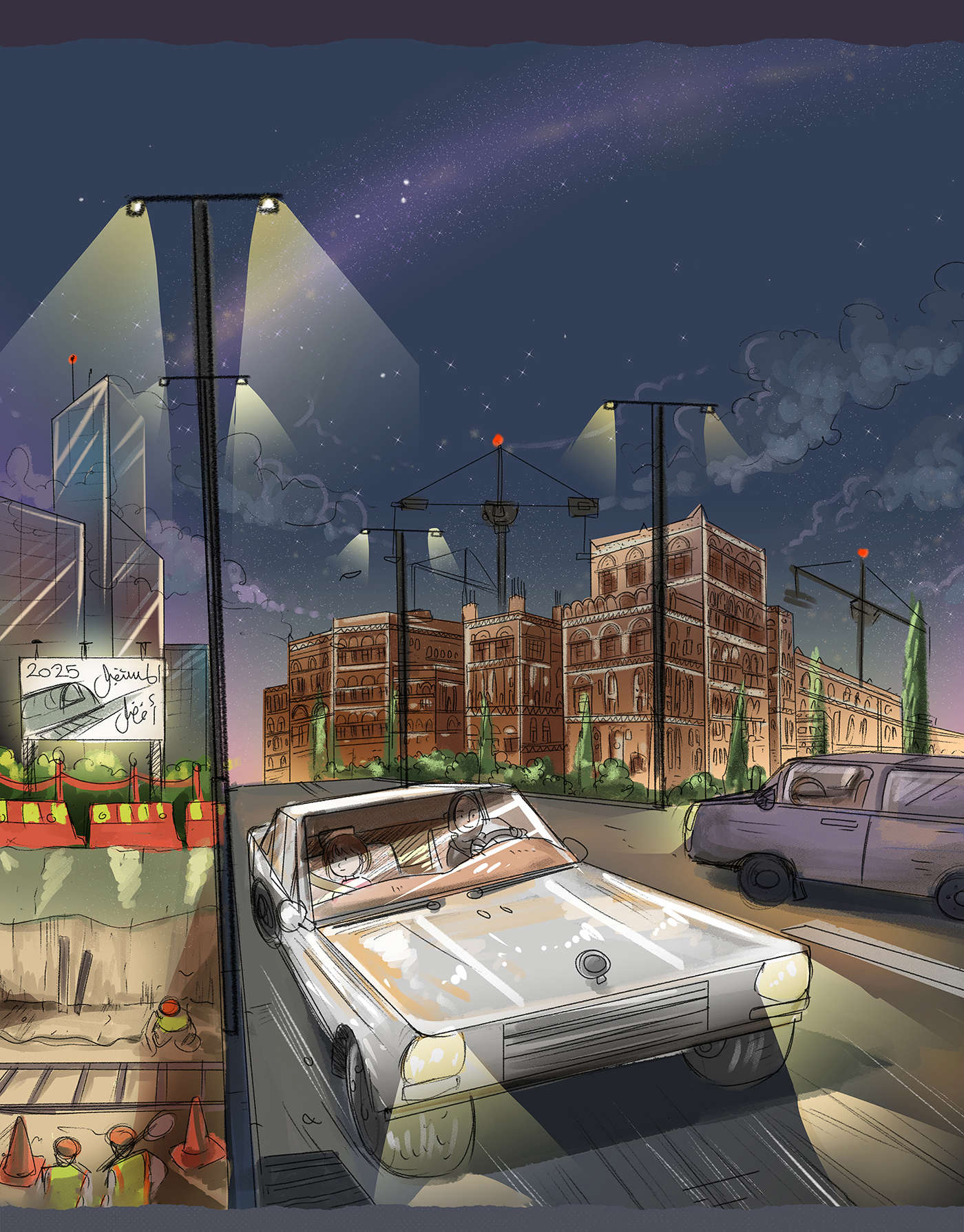

On our walk back to the car, I try to understand what’s going through Lamma‘s mind. Why this girl who is notorious for loving school is trying to get out of attending class.